Adult mountain pine beetles range from 4 to 7.5 mm in length. Source: Natural Resources Canada.

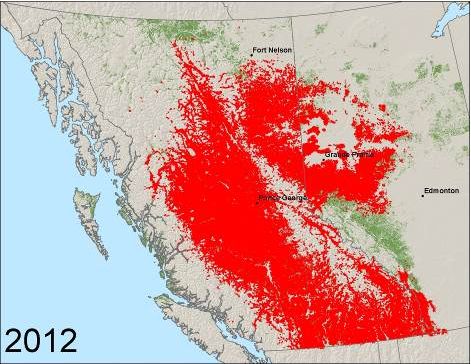

If you live in British Columbia, you’ve very likely heard about mountain pine beetle, or MPB. An outbreak of the insect starting in the late 1990s killed so many lodgepole pine trees that the forest-products industry in interior B.C. was devastated. The outbreak peaked in 2005 and largely subsided by 2017, once most of the mature lodgepoles pine had been killed. In all, the beetle affected about 180,000 square kilometers, an area about the size of New Brunswick plus two Nova Scotias.

An outbreak of the mountain pine beetle in BC starting in the late 1990s killed about 58 percent of the lodgepole pines in the province. Source: Natural Resources Canada.

The effects amounted to a “fundamental change in forest economies” that rippled through the province’s economy and is still being felt today, as a December 2022 CBC article explains. The impact of the MPB is exacerbating other problems, as a February 8 Canadian Press article explains: “Mill Closures Threaten to Punch Holes in the Fabric of Rural B.C. Towns.” The article, citing Statistics Canada data, reports that B.C. has lost more than 40,000 forest-sector jobs since the early 1990s.

MPB, which is native to BC, also attacks most other pines in the province, such as ponderosa, western white, and whitebark pine.

When the MPB population is low, healthy trees are able to defend themselves by producing large amounts of sticky pitch that can trap or push beetles out of the holes they bore into the tree. When large numbers of beetles attack a healthy tree, this natural defense can be overwhelmed. Once they bore through the outer bark, female beetles excavate tunnel-like egg galleries in the inner bark, or phloem. After they hatch, grub-like larvae build new galleries as they feed on the phloem. The many galleries disrupt the flow of water and nutrients carried by the phloem, weakening and eventually killing the tree.

Adult mountain pine beetle and larvae. Image: David McComb, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Together with large wildfires that burned through dead and dying stands of pines, the outbreak also changed habitat for species such as caribou. (SFI is working with numerous partners to conserve caribou across Canada.)

Large MPB outbreaks also have occurred in the western US, including Colorado, as a US Forest Service report explains.

The outbreaks in BC and the US were fueled in part by a changing climate. In the past, MPB usually produced one generation of young beetles per year, and populations were controlled by cold winter temperatures that killed most of the beetles. With longer, warmer summers, the beetles began to have two generations per year, and with warmer winter temperatures, more of the beetles survived to breed again the next year. What’s more, the MPB was able to survive at higher elevations where extreme cold had previously kept them at bay.

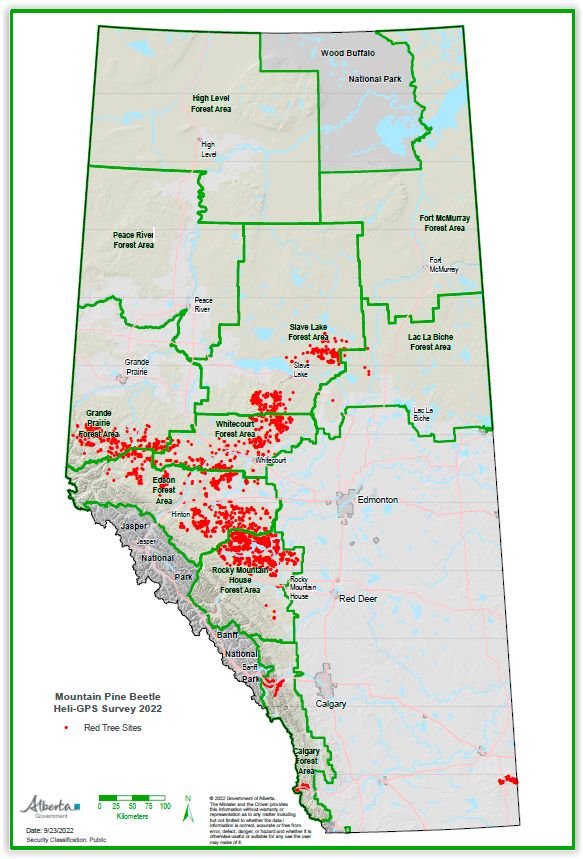

Until the early 2000s, the MPB outbreak, then the largest forest-insect epidemic in the history of Canada, was largely confined to BC: they could not survive the cold winter temperatures high in the Rocky Mountains. By 2005, the beetles had managed to cross the Rockies into Alberta, where they attacked not only lodgepole pine, but also jack pine, a species that is native across boreal Canada all the way to the Atlantic.

MPB detections in 2022. Source: Government of Alberta.

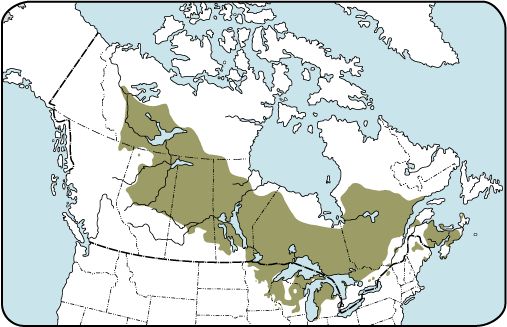

Today, the MPB is well established in Alberta, but has not yet progressed to the Yukon Territory or Saskatchewan; in 2013, MPB was found in the Northwest Territories, where warmer winter temperatures are allowing the beetle to survive and reproduce. According to the Invasive Species Centre, “the MPB could become a devastating invasive species if it reaches the pine forests in Eastern Canada.”

Some researchers say that the beetle could, in theory, expand into the eastern and perhaps even the southern US, where several species of pine are native.

The range of jack pine. Source: Natural Resources Canada.

In areas where an MPB infestation is detected (the beetle and symptoms of attack are described here), forest managers often harvest mature pines in and around the infested area, which helps limit the spread of the insect, as the BC Ministry of Forests explains. They also can harvest dead lodgepole, which has durable wood that can remain sound for several years after the tree dies.

Even if all lodgepole pines are killed in a stand, they can release many seeds, creating a new generation of trees. Because the MPB generally does not attack young pines, the new forest has a chance to survive, as long as the MPB population is low in that area. However, with temperatures continuing to warm, it seems likely that MPB outbreaks are likely to return to B.C.’s forests.