By Michael (Mike) Martini, Director of Urban and Community Forestry for the U.S.

For decades, urban foresters have played a vital role in maximizing the economic, environmental, and social benefits provided by city trees and green spaces. However, the work has taken on even greater profile and urgency in recent years amid the climate crisis and environmental justice concerns in the U.S. and abroad.

With the recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act allocating $1.5 billion for urban forest projects, the sector now has an unprecedented opportunity to strengthen its importance on a national scale. As cities strategically invest in planting, maintaining, and equitably distributing tree canopy cover, urban foresters have the chance to demonstrate tangible impacts on metrics like employment, community engagement, public health, and climate mitigation–paving the way for continued investment in this vital work.

Getting My Start

When I first went to college, I had no idea urban forestry would become my life’s passion. I started as an engineering major and bounced around in a few other majors like environmental science and ecology, knowing that I wanted to work outdoors and with people, but not quite sure what the right fit was. Then, I met Dr. Jason Grabosky, who was starting Rutgers University’s new urban forestry program. He opened my eyes to the exceptional intersections of trees, people, and communities that this field encompasses. I was hooked as he shared all the different career possibilities–from arboriculture to inventory to greenhouse management.

Now, many years later, I can see how that pivot toward urban forestry set me up for a deeply rewarding career. Urban forestry allowed me to spend time outdoors while making a tangible positive impact. As the Director of Urban and Community Forestry for the U.S. at SFI, I am driven by a core belief that solving the challenges in urban forestry requires collaboration across communities, disciplines, and regions.

The Intersection of Trees, People, and Communities

One of the biggest misconceptions I constantly encounter is the perception that “trees aren’t political.” I would argue trees are among the most inherently political forces in our public spaces and civic dialogues. Everybody has a strong opinion about trees–whether questioning why a particular tree was planted in that specific location, advocating for more trees on their street, or vehemently opposing a scheduled removal. Further, like trees, many of today’s major challenges–climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution–are global issues that transcend any artificial divisions we’ve created as humans. They cannot be effectively addressed within the boundaries of a single city, state, or country alone.

So, my journey into urban forestry wasn’t just about trees; it was about people and their communities. Trees don’t recognize the boundaries we create, so our approach to managing urban forests must be interconnected. At its core, urban forestry is about relationships between trees and people, past and future stewards, the community, and the environment. I feel fortunate to play a role in tending those connections daily. It’s deeply gratifying work that blends my interests in the outdoors, community work, and creating a resilient green legacy for generations to come.

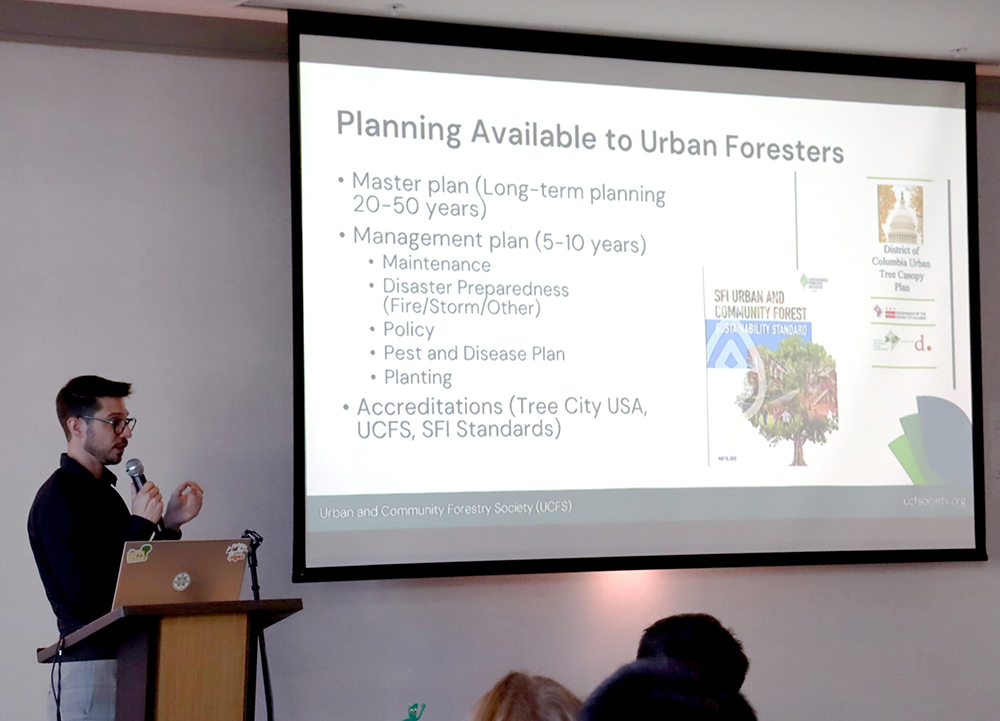

My goal at SFI is to inspire collaborative forest-focused leaders who can work together across departments, cities, and regions all over the U.S. I envision municipalities developing their own urban forest management plans, but then coming together to create an overarching regional plan. By using SFI’s new Urban and Community Forest Sustainability Standard as a common language and framework, we can help facilitate this cross-boundary cooperation.

Too often, those working across the sector operate in parallel tracks, utilizing the same technical vocabulary, but inadvertently ascribing different meanings to the same terms. The SFI Standard equips us with a new opportunity to get on the same page terminologically while developing deeper emotional intelligence skills. We speak knowledgeably about tree ordinances and permitting processes but fail to grasp how those well-intentioned policies and protocols can generate apprehension, alienation, and opposition from the very people we aim to serve.

We need to deeply engage with communities themselves, meeting people where they are. My approach is to have open conversations, listening to people’s real concerns first before even bringing up trees.

Are you worried about maintenance costs and liabilities? Afraid of losing access to sufficient water for new plantings? Deeply suspicious after past negative experiences with city initiatives? We have to understand and address those core issues before we can make progress. Once we build trust, we can explore how urban greening aligns with residents’ priorities for their neighborhood.

That’s why partnerships with nonprofits like the Arbor Day Foundation are so powerful–they can help make those community connections in an authentic way over the years, not just in one-off meetings. By the time we get to discussing urban forest management, we’ve built trust and understanding of what’s important to that neighborhood. At the same time, groups like the Urban and Community Forestry Society can equip professional urban foresters with skills for communicating effectively with the public, politicians, landscape architects, and others.

Another focus of my work is promoting robust forest literacy and career pathways from diverse backgrounds in the urban forest sector with supporting materials and programming delivered with support from Project Learning Tree (PLT), an award-winning educational initiative of SFI.

Survey data about the identities of International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) members shows that the average urban forester is aging and nearing retirement. Among the ISA members surveyed, 80% were male, and 75% were aged 35 or older, with a slight skew towards the 50-59 age bracket for urban foresters specifically. To address this impending workforce gap, there is a need to attract younger professionals from diverse backgrounds and experiences who can better understand and cater to the unique needs and priorities of different communities. This could involve creating more opportunities for apprenticeships, micro-credentialing, resume workshops, and other supportive initiatives to reduce barriers to entry into the urban forest career path.

A Vision for the Future

My aspiration is that five years from now, we will have facilitated the emergence of interconnected regional networks of cities actively collaborating together on projects and initiatives–all using the common language and guidance framework provided by the SFI Standard. I envision certified urban forestry “ambassadors” who have successfully guided their own communities through the process, now devoting time to mentoring and supporting neighboring municipalities on their own certification journeys.

I dream of a sector-wide evolution where we fully embrace the understanding that our work fundamentally transcends any single vocational silo– it is inherently multidisciplinary, drawing vital insights from fields as diverse as public health, community development, ecology, and social justice where we fully internalize that we do not just serve trees, but entire communities of people for generations to come.

I see a future where robust urban forest management plans are jointly developed and resourced across multi-city regions. A future where we proactively build cooperative programs and resource-sharing arrangements to deploy our limited funding and personnel as efficiently as possible toward mutual priorities.

But most importantly, I hope for a future where urban forestry is sustainably rooted in authentic relationships and selfless service to communities. Where we fully embody the spirit that got many of us into this line of work from the start–a deep appreciation for the connective power of trees to bring people together, beautify and uplift neighborhoods, and nurture the bonds between human societies and the natural ecosystems we mutually rely upon.

The SFI Urban and Community Forest Sustainability Standard provides us with a powerful tool to make this vision a reality with PLT ’s environmental education, forest literacy, and career pathways resources. But the real work, as always, will come down to each of us breaking free from insular tendencies and embracing a radically collaborative, community-driven, interdisciplinary approach to caring for urban forests. If we can spend the next few years embodying that spirit of partnership, the future of urban forests will be bright.

Learn more at forests.org/UrbanStandard and download the SFI Urban and Community Forest Sustainability Standard in English, French, and Spanish.