US Fish and Wildlife Service: Tortoise No Longer Candidate for ESA Listing in Most of Its Range.

This article was originally published in The Forestry Source. Author: Wilent, Steve. Title: “Managed Forests are Key to Gopher Tortoise Conservation,” The Forestry Source. March 2023, Vol. 28, No. 3; page 1 – 3. © The Society of American Foresters.

By Steve Wilent

Most news articles involving the Endangered Species Act (ESA) describe proposals to list specie

s as threatened or endangered, or the decline of those already listed. In October, a decision by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (F&WS) offered some positive news: The population of the gopher tortoise in the southeastern United States is robust in most of its range and is no longer a candidate for listing as threatened under the ESA.

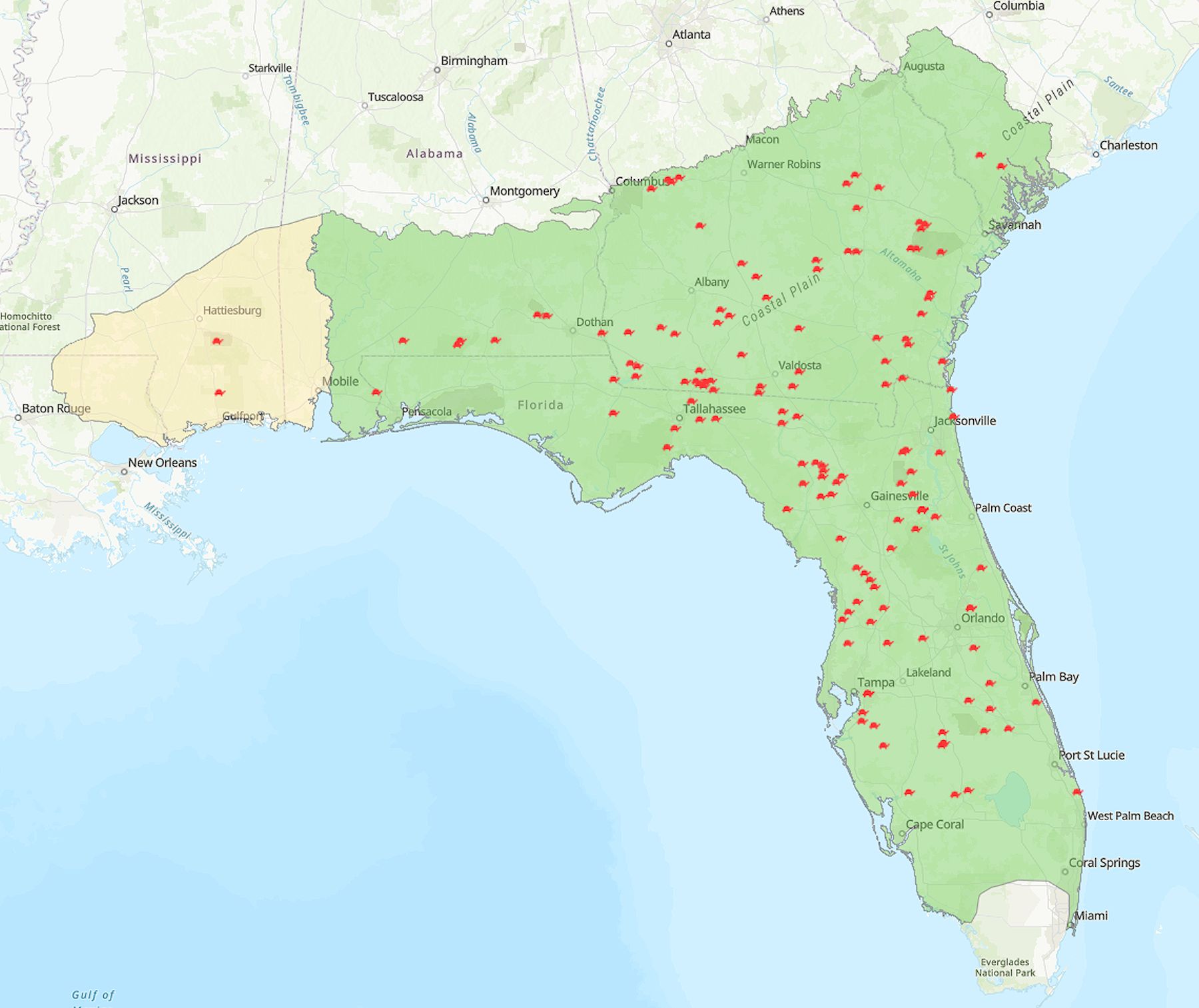

The range of the gopher tortoise, the only native tortoise east of the Mississippi River. Photo credit: US Fish and Wildlife Service.

The gopher tortoise lives primarily in forests throughout Florida, southern Georgia, and portions of South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and eastern Louisiana. They excavate burrows up to 12-feet deep that provide shelter from wildfire, predators, winter cold, and summer heat. Gopher tortoises can live to be 50 to 80 years old and can grow to be up to 15 inches long and weigh from eight to 15 pounds. They are primarily herbivores, but sometimes eat insects and carrion.

The F&WS listed the gopher tortoise in 1987 as threatened under the ESA in the western part of its range, in portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. In 2011, the agency determined that the gopher tortoise warranted listing as a threatened species in the eastern portion of its range, where the vast majority of tortoises live, but the agency opted not to list the species there because it had higher priorities for other species.

With the October F&WS decision, the species is no longer a candidate for listing in the eastern portion of its range; it remains listed as threatened in the smaller western portion of its range.

In a Federal Register notice of its decision, the F&WS noted that active forest management and efforts by a range of public, private, and non-governmental partners play a key role in gopher tortoise conservation.

Heidi Miller, daughter of Dr Darren Miller, vice president of forestry programs at the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement Inc. (NCASI), with a gopher tortoise. Photo credit: Darren Miller

“I think it’s a big win for active forest management, for forest landowners, and many other public and private partners who’ve worked hard for literally decades to help support the conservation of the gopher tortoise through voluntary conservation efforts,” said SAF member Jimmy Bullock, senior vice president, forest sustainability, for Resource Management Service (RMS). “There is no doubt that forest management practices in the southeast have changed as ownership has changed from companies that were primarily growing trees for pulpwood to owners that are now growing trees for sawtimber and poles, with multiple thinnings and other activities that provide more open canopy conditions for encouraging herbaceous groundcovers. That has contributed tremendously to gopher tortoise numbers, to viable gopher tortoise populations increasing across the landscape.”

RMS, a Birmingham, Alabama-based timber investment management organization, manages nearly 2.2 million acres of forest in the US Southeast, all of which is certified under the Sustainable Forestry Initiative or Forest Stewardship Council forest management standards.

In its Federal Register notice, the F&WS cited research showing that, in commercial pine forests where suitable conditions are not maintained, gopher tortoises more frequently abandon burrows and move away from the low-quality habitat of closed-canopy stands. However, stands managed more intensely for traditional wood products incorporate management strategies that generally have the open canopy conditions tortoises need. “For private lands, programs such as forest certifications (e.g., Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) or Forest Stewardship Council) and the development of diversified markets for forest products have increased forest management practices that benefit gopher tortoises,” the F&WS reported.

An estimated 13.7 million ac (5.5 million ha) within the gopher tortoise’s range are certified through SFI.

The American Forest Foundation has long collaborated with the F&WS and other partners to promote gopher tortoise conservation. In 2008, the foundation published Pine Ecosystem Conservation Handbook for the Gopher Tortoise in Florida: A Guide for Family Forest Owners.

Managed pine stands like this one have open canopy conditions that encourage the growth of herbaceous groundcovers that provide forage for gopher tortoises. Photo credit: Darren Miller.

Conserving and Increasing Habitat

The main threats to the gopher tortoise are habitat fragmentation and destruction, including through development and urbanization. However, about 80 percent of potential gopher tortoise habitat is on privately managed forest lands. In its Federal Register notice (https://www.regulations.gov/document/FWS-R4-ES-2009-0029-0069), the F&WS noted that “many larger private working forests … accomplish conservation within a broad network of collaboration with Federal, State, and local government agencies, universities, and non-governmental organizations. For example, forest landowners may create and maintain areas of open pine conditions, conduct gopher tortoise burrow surveys, conduct research, and implement BMPs [best management practices] that benefit the gopher tortoise.”

The Florida Forest Service (FFS) uses such techniques and others on the more than one million acres it manages (492,000 acres of which is SFI-certified). In gopher tortoise habitat, typical forest management activities, including timber harvesting, prescribed fire, thinning, reforestation, and so on, are allowed, said Brian Camposano, assistant chief of the FFS’s Forest Management Bureau.

“Of course, we always do what we can to flag gopher tortoise burrows, so loggers can avoid them with their equipment,” said Camposano. “But there’s no permit required for these operations [related to the gopher tortoise], because these are beneficial practices. Thinning is beneficial. For example, you don’t want an overly dense stand. With a closed canopy, the vegetation that the gopher tortoise relies on won’t grow.”

Despite the F&WS decision, the state of Florida still lists the gopher tortoise as threatened. Both the tortoise and its burrows are protected under state law. Other states also have laws or regulations protecting the species. In Florida, gopher tortoises must be relocated before any land clearing or development takes place. To do so, a property owner must obtain a permit from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission for moving the animals, and must engage a gopher tortoise agent authorized by the commission to handle and transfer the tortoises to registered recipient sites.

Recipient sites must have suitable vegetation for sustaining tortoises and the deep, sandy soils they require for burrowing, with water tables deep enough so that burrows do not flood. Recipient sites also must have adequate habitat to support both relocated tortoises and those already in residence.

Prescribed fire is often used to eliminate shrubs and small trees that the tortoises don’t or can’t feed on, but that also shade out vegetation they do need. This stimulates the growth plants and grasses that provide nutritious forage for the tortoises.

“Prescribed burning is huge,” Camposano said. “For any recipient site, you’re going to have to keep it burned to maintain a diversity of groundcover. Gopher tortoises definitely need some open ground and not a lot a whole lot of shrubs and midstory trees, and fire is a key tool for maintaining those conditions. The best thing we can do for gopher tortoises is relocate them to sites with well-drained sandy soils for burrowing and use fire for maintaining their food supply.”

Gopher tortoises can thrive in stands with any mix of pine species, including longleaf, loblolly, and slash pine, but they also can survive in xeric oak hammocks, scrub, dry prairies, and coastal dunes, and a variety of disturbed cover types such as pastures and even urban areas.

A Win for Science and the ESA

Gopher tortoises grow to be up to 15 inches long and weigh from eight to 15 pounds, according to the US Fish & Wildlife Service. They excavate burrows up to 12 feet deep that provide shelter from wildfire, predators, winter cold, and summer heat. Photo Credit: US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Dr. Darren Miller, vice president of forestry programs at the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement Inc. (NCASI), agrees that the improved status of the gopher tortoise is a win for active forest management. NCASI’s mission is “to serve the forest products industry as a center of excellence providing unbiased, scientific research and technical information necessary to achieve the industry’s environmental and sustainability goals.”

“It’s also a win for using the best available science, as required by the ESA, and it’s a win for collaborative conservation,” Miller said. “We would not have gotten to this point without the US Fish and Wildlife Service, state agencies, private forest landowners, and a variety of research organizations—universities and others—working together. Because of this collaboration, we can document the security of the species across large portions of its range. This didn’t happen overnight—this has been a long process.”

The Georgia Gopher Tortoise Conservation Initiative, for example, is a collaboration of state and federal agencies, conservation groups, for-profit companies, foundations, and landowners.

“The other thing that I think is really interesting about this is how proactive some of these organizations became when the species was proposed for listing,” said Miller. “People have been working for a long time toward improving management for the species on public and private lands, and all that effort has really paid off, not only for landowners and for the service, but also for the species.”

Miller says that understanding the management of gopher tortoises on private land in the southeast is very important, given that 89 percent of forestland in the southeast is privately owned.

“Gopher tortoises need forests where there’s a lot of light penetration to the ground and where there’s a lot of green vegetation close to the ground, at tortoise height. And many other species depend on those open-canopy conditions as well,” he said. “Moving from growing pulpwood to sawtimber means you have fewer trees per acre, and one or more thinnings over time that promotes those conditions. … Young forests and regeneration harvests also provide those conditions. What’s important is the persistence of the species over the long-term, and a lot of private timberland blocks have had gopher tortoises on them for many years.”

Additional research is needed, Miller said.

“Tortoises are very long-lived, so you may have situations where you have adult tortoises that aren’t reproducing. We need to look at that not just on private lands, but across the species’ range. There’s been some interesting research that show that tortoises may have different clutch sizes and different abilities to reproduce, based on where they are in the southeast, but we don’t yet fully understand why this occurs,” he said.

Additional knowledge about the response of gopher tortoises to management activities also is crucial.

“On a managed forest landscape, habitat conditions change over time. Maybe an area starts out as being not suitable habitat for tortoises, then moves to suitable, and then it goes back the other way, depending upon where you are in the forest-management cycle. Understanding how gopher tortoises respond to that would be of value.”

A better understanding of the gopher tortoise and its habitat needs will not only help forest managers promote gopher tortoise conservation, but also keep the species off of the federal threatened list in the future and perhaps convince Florida to reclassify the species.

“I think this is a win for the ESA. This is how the act is supposed to work,” said Dr. Darren Sleep, Lead Scientist at SFI. “We’re supposed to list species that are in trouble and not list species that are not in trouble. At the beginning of this process, the US Fish and Wildlife Service did not have the information needed to be able to say that the species was not in trouble. But now that they’ve got that information, because of the collaborative effort to manage the species, because research organizations participated, because private landowners stepped up, and because so many of those private landowners are SFI-certified and thus can demonstrate that they are managing forests in ways that benefit the tortoise—all this works together to build trust and to definitively show the Fish and Wildlife Service that the gopher tortoise is not in trouble. So I think this is a win across the board.”

Steve Wilent is the director of sustainability communications at The Sustainable Forestry Initiative.